If necessity is the mother of invention, obsolescence might be the mother of ingenuity. Bill Degnan, owner of the newly opened Kennett Classic vintage computing gallery and gift shop at 126 South Union Street, not only brings the history of computing alive—he also employs a combination of experience, knowledge, and up-to-date technology to bring old computers back to life.

Bill’s initial interest was sparked in the mid-1990s, when he wanted to get a file off an old 5¼” floppy disk but couldn’t find a computer with a disk drive that was still compatible. “It struck me then that technology becomes outdated so quickly and then it’s gone,” he says. “I decided to go to the farmers market to see if I could find people selling older machines to read older disks and to see what was available.” An exhibit at the Smithsonian kindled his curiosity further. “I was familiar with Apple and IBM, of course,” he says. “But being a historian type I was interested in how computing told a larger story of our economic, social, and political history.”

Bill, who taught a computer history class as an adjunct at the University of Delaware for four semesters, initially worked with Karen Doneker to create a unique experience for visitors to Kennett Classic. Karen, a social scientist with a PhD in family studies and human development is also a professor at Towson University. “I’m fascinated by the ways that technology has changed—and continues to change—family interaction,” Karen says. She loves the “kitchen table stories” shared by those whose pioneering work in the field forever changed how we live.

The computer history exhibit at Kennett Classic shows how technology has helped to shape us and the world we live in.

Bill loves going on what he calls “computer rescues” of donated equipment. These rescues involve cataloguing and caring for the machines as well as hearing and recording the personal connections and reflections of those who worked with, and saved, the machines—stories that will be lost if they’re not documented and preserved.

I was interested in how computing told a larger story of our economic, social, and political history.

—BILL DEGNAN

The rare assemblage of vintage machines and memorabilia at Kennett Classic tells the story of computer history in a way that connects the technical with the human. Bill enjoys sharing his knowledge and making the technical elements of computing understandable and accessible for all. “Those who aren’t hobbyists can also appreciate what’s here and not be overwhelmed,” Karen says. “Lots of computer museums feature rows of computers without context.” As a result of their collaborative curation, visitors to Kennett Classic have the rare opportunity to see the history of modern computing and how it was shaped by, and helped to shape, the world we live in.

The 1977 Apple II originally ran its programs from cassette, but most Apple II owners upgraded their systems to include disk drives, as pictured here. The display for the Apple II was a color TV set.

Time Travel

Depending on your own vintage, a visit to Kennett Classic might feel like a trip down memory lane—as you see how your own story intersects with the bigger picture of technology’s advances over the past seven decades or so. But even Gen Zers, for whom it’s all prehistory, are rediscovering the art and fascination of vintage computing and its evolution through the years.

A young visitor to Kennett Classic plays a video game on a vintage Apple computer.

“We can see the first spark of modern computing,” Bill explains, “in the IBM 701, circa 1952.” He points out a copy of Edmund Berkeley’s Giant Brains (1949), which described in accessible terms how to make a computer. The display includes original hand-coded program listings from an IBM 650, which as a result of special marketing to colleges helped to secure the company’s dominance in the market; tube modules from the UNIVAC II (which enabled the US government to store and tabulate the mountains of data); a Donner 3500 (c. 1959), one of the oldest working portable computers in the world; and the manual for the H316 Honeywell kitchen computer (which retailed for $10,000 in 1969). There’s even a copy of Radio Electronics from May 1967, which made the astounding prediction that someday everyone would have a computer in their home. On display as well are curiosities like a 1970s home computer that was actually built into a desk, Xerox Alto components (the first computer to support an operating system based on a graphical user interface), and early home computers from Radio Shack, Commodore, and Apple II (1977).

“The Apple II Plus, which we have set up for visitors to sit down and use, has a video pinball machine and other games ready to play,” Bill says. Kennett Classic also houses an IMSAI 8080, the computer used in the 1983 Matthew Broderick film WarGames. “Some of the actual items on display in our gallery were used in movies, books, and television, including a presentation at the US Senate, the movie X-MEN Apocalypse, Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation with Mo Rocca, Wired Magazine, the BBC, and the television show Halt and Catch Fire. We get requests to provide vintage computing items somewhat regularly,” says Bill.

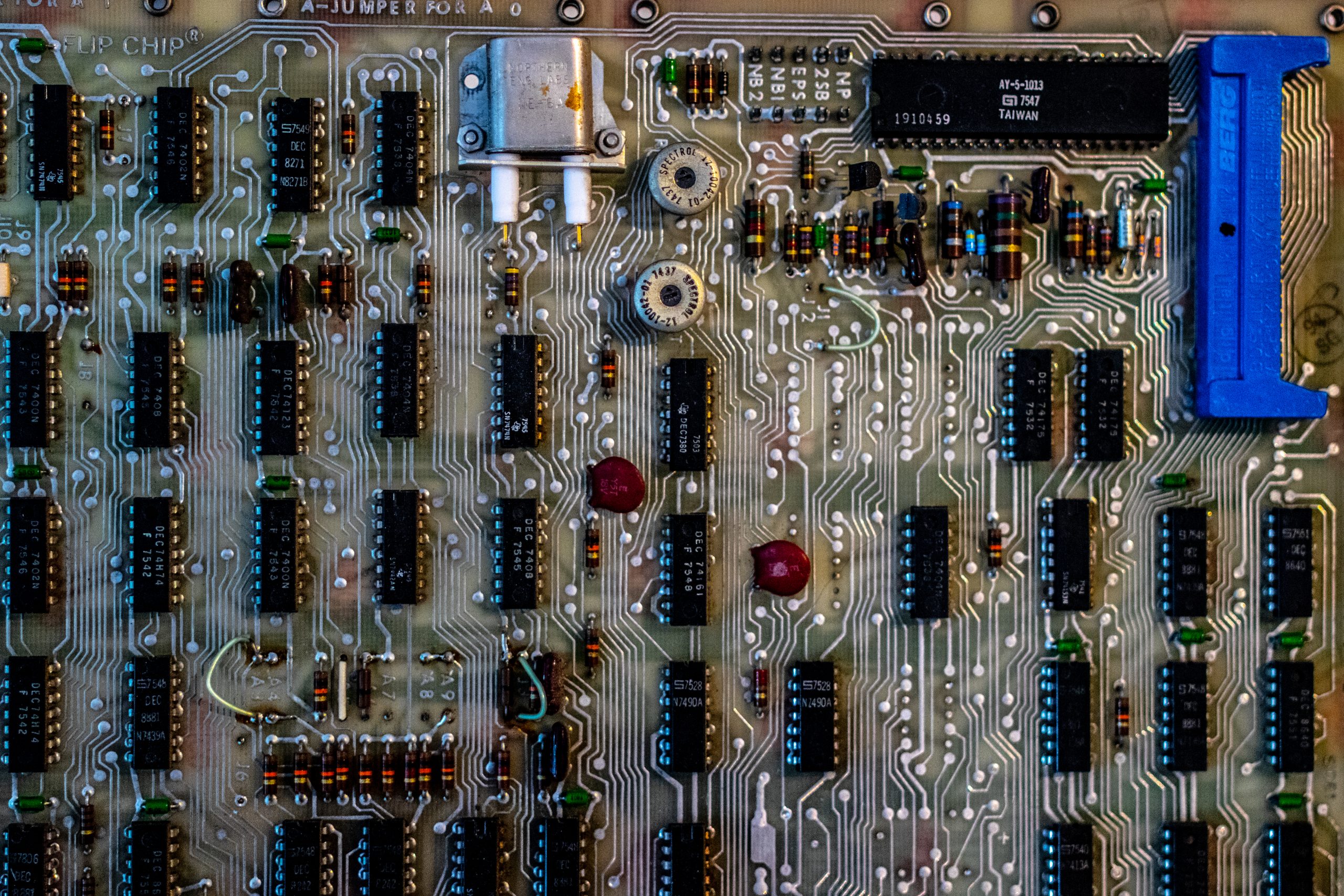

Kennett Classic is an interactive experience, too. Bill is happy to “fire up” some of the computers for those who are interested. Digital Equipment Corporation’s PDP8e, for example, cost about $40,000 in 1970 and was often used to teach coding—and it was shipped to universities loaded with the first-ever video game—Spacewar—which students stayed up all night playing. Also on display is the December 1972 edition of Rolling Stone which features an article by Steward Brand called “Spacewar: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums.” The more things change . . .

Digital Equipment Corporation’s PDP8e shipped to universities in 1970 loaded with Spacewar, the first-ever video game.

Again, it’s the careful curation of the exhibit that makes the overall story clear. “It’s not just about what technology does, but about how humans interact with technology,” Karen says. “All of the extant bits and pieces aren’t worth anything until they’re assembled into a cohesive whole to show how each piece fits in the history,” Bill says.

In the US, this history begins with initial conceptual questions, the building of the atom bomb, and running power plants and DuPont factories. “As you march into the 1970s,” Bill says, “you see smaller companies developing computer technology for medical, insurance, and legal applications.” It was the Japanese, he says, who drove miniaturization and focused on small, compact machines that used less power. All of this, of course, sheds light on the devices and diverse applications that are such an integral part of our lives today.

The 1965 Friden model 132 Electronic Calculator was the first commercially-available solid-state desktop electronic calculator with a single-key automatic square root function.

Commodore:

A Local Computer History Connection

“What’s on display is a fraction of our entire collection,” Bill says. “We switch elements out and create a new display every three months so there’s always something fresh to see and to learn about.”

One exhibit, for example, featured computers manufactured by Commodore International, whose headquarters were in West Chester. Chuck Peddle, who died in 2019, designed the processor for the Commodore PET. Commodore was instrumental in bringing computers into homes. The exhibit included rare pieces, including some prototypes that were never sold. “Even people from Commodore have never seen some of these things,” Bill says.

At the Vanguard of Web Design—

and Vintage Computing

In 1995, Bill says, he looked in vain for a web designer. “There was no section in the yellow pages for web design,” he says, “and I knew it would be big, so I taught myself how to do it.” He smiles. “It was cutting-edge back then.” He started his own company, and 25 years later Degnan Co. Consulting continues to offer a full range of web design and programming services.

As a musician and someone who’s “always liked to do my own thing,” Bill says this career has suited him perfectly. It’s also enabled him to collect and restore older machines. And this “day job” pay the bills as he launches Kennett Classic—a new endeavor that’s the culmination of years of tracking down and collecting pieces of this history. “He knew these things would matter,” Karen says, “even when he didn’t know why yet.”

“The reason it’s impossible to find 1960s computers that work is because they’ve spent 60 years in a basement or some other environment that’s not temperature controlled,” Bill says. Often, though, they only require cleaning and replacing or replicating small parts. “All computers are interesting—old and new. It’s like fixing up an old Camaro. After work, computer guys work on more computers. Running them preserves them and keeps them fresh,” Bill says. “And the only way to keep this going is to teach it.”

His VintageComputer.net website focuses on how to repair old computers. “The future of vintage lies in sourcing, emulating, and reproducing parts. No one has phone lines anymore for a modem connection, for example, so it means tricking the computer into connecting to wifi.” There’s been a rebirth of the hobby, he says, as a result of this emulation and new electronics and the ability to, for example, archive software so it can be downloaded from the internet. “It might be cheating to connect vintage computers to the modern world,” Bill says, “but it brings a new generation into it.” In addition to cards, prints, and vintage tech-themed gifts, the Kennett Classic shop also sells devices to enhance and emulate computer parts to bring vintage machines back to life.

It’s not just about what technology does, but about how humans interact with technology.

—KAREN DONEKER

Bill has gladly received many donations with fascinating stories—for example, a device the donor’s grandfather invented in 1979 to read Morse code. “If anyone has 1960s mainframe hardware, I’d display it immediately,” he says. He’s also looking for a donation of a card reader. “They don’t even have to work,” he says. “We’ll attempt to fix them at our next workshop.”

Through the Kennett Classic Meetup group, whose mission is “to preserve computing history through hardware restoration, software archiving, documentation and education,” Bill connects with others who have an interest in computer history (“vintage” computers are generally those built before 1994).

The gift shop at Kennett Classic features prints, mugs, ties, socks, and other techie-themed items.

Kennett Classic is located at 126 South Union Street, Kennett Square.

Bill is happy to be in Kennett Square, with all of the shops, restaurants, and places to explore locally. “I spent a long time looking for the perfect location,” he says. “Kennett Classic is one more thing to engage people here in town, both residents and visitors—another reason to come to Kennett Square.”

kennettclassic.com

vintagecomputer.net

Photos by Dylan Francis