Your grandmother or great-grandmother may have entertained a travelling salesman armed with a gun and carrying a suitcase made of vulcanized fibre—to demonstrate the astonishing strength of this revolutionary material. “It’s harder than horn, lighter than aluminum!” a salesman would assure his audience as he shot bullets at the impenetrable case.

And if your grandfather or great-grandfather went off to fight in World War II, he may have carried such a suitcase or flown in a plane carrying life-saving auxiliary fuel in a vulcanized fibre gasoline tank while his family at home used ration tokens made of the same material. The tagline of the National Vulcanized Fibre Co. (NVF) was “material of a million uses.” And if you’re a local, you or someone in your family may have worked at the NVF plant here in Kennett.

As discussions begin anew about the best uses for the former NVF site on Mulberry Street in Kennett Square—the largest undeveloped parcel of land in the Borough’s square mile, we thought it would be interesting and helpful to look at some of the history behind the Kennett NVF plant. The Kennett Square we know and love today was a hub of innovation and shaped in large part by its role in the Industrial Revolution. The American Roads Machine Company, for example, was on the site of the former Genesis building at 600 South Broad Street—which is the future home of the Borough offices and the Kennett Square Police Department. The NVF plant on Mulberry Street once played a significant role in the local economy, too. At one time it employed 250 local people—not all of whom could live in Kennett Square due to housing shortages—and shipped its products worldwide.

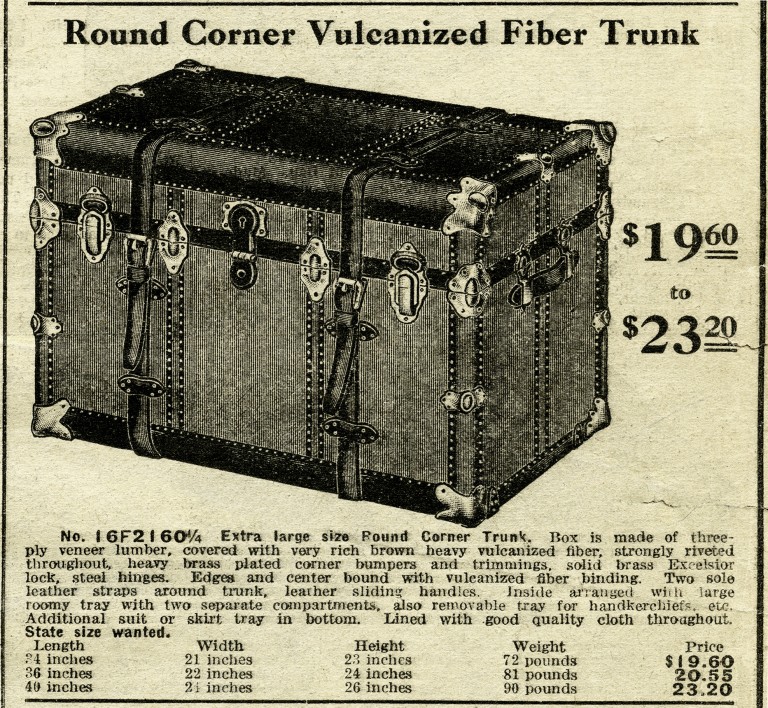

An ad from the 1916 Sears Roebuck and Co. winter catalogue for a trunk covered with vulcanized fibre.

What is Vulcanized Fibre and Why is it Important?

Vulcanized fibre, or indurated paper as it is sometimes called, is made from layers of paper soaked in zinc chloride which merge into a single thick celluloid layer. The resulting material is plastic-like but has a higher melting point. A 1955 newspaper article toted it as “the strongest material per unit weight known to man.” Vulcanized fibre had a variety of household uses besides suitcases and ration cards—including insulation, trash cans, and steamer trunks. Because of its electrical and mechanical properties and durability, and because it and didn’t crack, split, or corrode, it also found many uses in camera parts and circuit boards. A large percentage of the world’s supply of the latter, at the height of the computer boom in the 1970s and 1980s, were manufactured at NVF’s Kennett plant.

Like most chapters of human history, the story of NVF is complicated. It’s a story of innovation and of economic development and progress, and even of early recycling and repurposing, as the early paper used to produce vulcanized fibre (before the process for making paper from wood pulp was perfected) was made out of discarded linen and cotton rags. The company developed methods for recycling the water used in the process as well. There was a vulcanized fibre display at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, and this cutting-edge material also played a key role in the mass production of electrical appliances and in the successful and dependable operation of railroad signal systems.

In the shadow of the mighty DuPont Chemical, NVF’s history is often forgotten, but Kennett can claim one of the only non-DuPont manufacturing sites in the area that was also at the forefront of innovation. Like many other industrial manufacturing companies, NVF also had its share of workplace injuries and left in the wake of its bankruptcy not only hundreds of families devastated by unemployment, but also a site dangerously polluted by toxic chemicals.

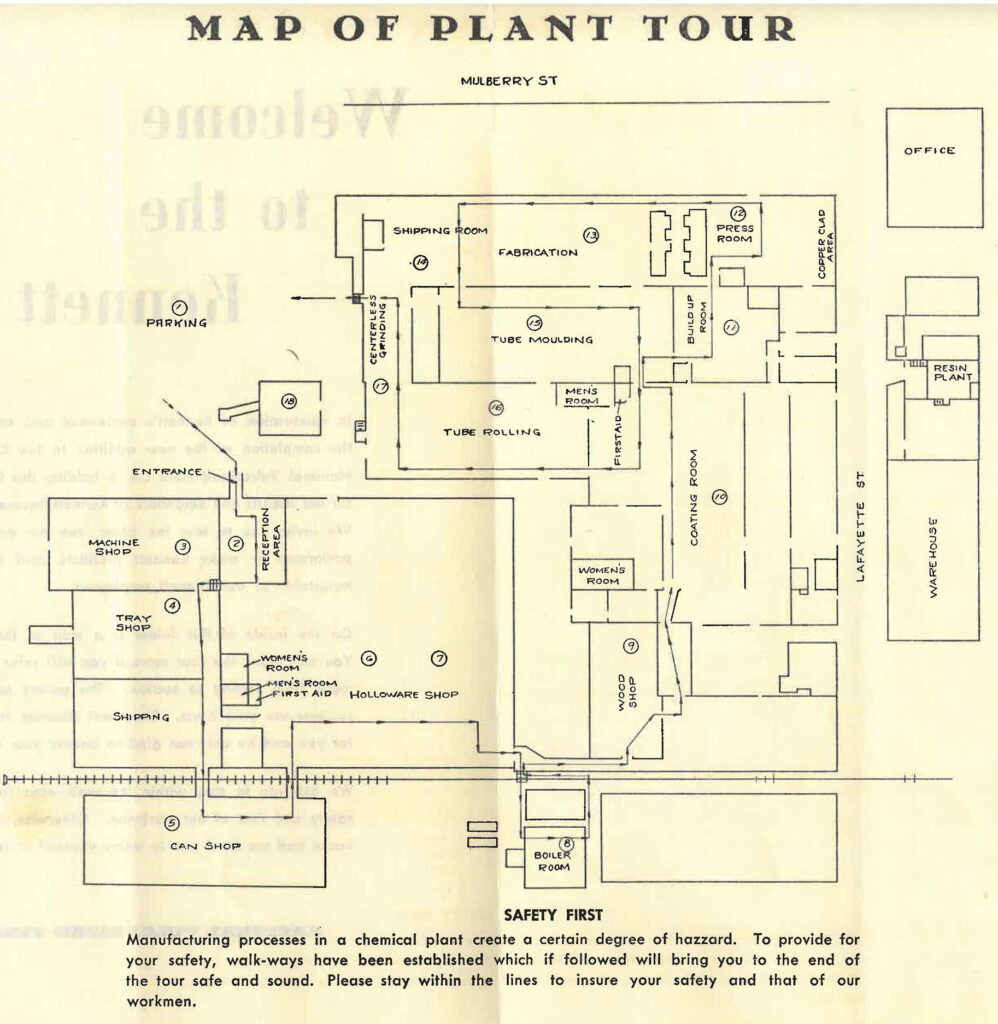

This map of the Kennett NVF plant was provided to visitors at a special open house to celebrate the plant’s centenary.

It All Began at a Gristmill

The history of NVF has deep roots in Kennett history and begins with one of its early and prominent families, the Marshalls. In 1763, John Marshall built a grist and sawmill at Marshall’s Bridge on Red Clay Creek, on present-day Creek Road. In 1856, John’s grandson Thomas converted the gristmill into a paper mill. Thomas’s two sons, Israel and T. Elwood, renamed the company Marshall Bros. and expanded over the state line into Delaware, at Auburn Mills in Yorklyn.

In the 1890s, innovative businessman and inventor Israel Marshall decided that since some of his customers were buying his paper to make vulcanized fibre, a process patented by Englishman Thomas Taylor in 1859, he would be well positioned to get into the business too. A frequent visitor to other paper mills, he saw the inefficiency of paper production and took notes on various processes. At the mill in Yorklyn, paper production continued apace on the first floor while on the second floor, behind blacked-out windows, Israel invented a continuous fiber machine so he could make rolls of paper that no one else could make. With this invention, Israel Marshall revolutionized vulcanized fibre production and set his local enterprise on the track to becoming an international leader in the industry.

In 1898, the Marshall brothers built another vulcanized fibre manufacturing plant in Kennett Square. Over the decades, through various expansions and mergers, the company that began as Marshall Bros. eventually became the National Vulcanized Fibre Company (NVF) in 1922. NVF grew exponentially under the leadership of George B Scarlett and became one of the three largest fibre companies in the country with manufacturing sites in Wilmington and Newark as well as Kennett, Yorklyn, and Toronto, Canada. As a newspaper article in 1924 claimed triumphantly, “it looks upon the world as its market, recognizing no seas, no boundaries.” The Kennett plant produced, among many other products, durable and seamless cylindrical cans to catch cotton or wool in spinning mills. In the 1920s, the company’s floor area, which covered over five acres, was declared “the largest unbroken floor space of any plant in Eastern Pennsylvania.”

In 1966, Victor Posner became the majority shareholder of NVF stock. He named himself president and chairman of the board and used NVF as a holding company for other businesses. Many of these companies began to fail, and NVF filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1993 and again in 1999. Posner died in 2002, and NVF filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in 2007. The property was purchased by George Beer’s Delaware Valley Development Company (DVDC) in 2009.

The former NVF site on Mulberry Street was the scene of a fire in March 2010.

What Next?

Kennett Square is not alone in facing the questions, challenges, and opportunities presented by its former NVF site. Three NVF sites in Delaware—in Yorklyn, Wilmington, and Newark—are all in various stages of clean-up, re-envisioning, rezoning, and repurposing. Through a public/private partnership, the former NVF site at Auburn Valley State Park in Yorklyn, Delaware, has been successfully cleaned of zinc chloride, the main pollutant at that site and the chemical used to create vulcanized fibre. While zinc chloride is not particularly harmful to humans, it’s very detrimental to the ecosystem. Over 75,000 pounds of zinc chloride were removed from the groundwater, along with an additional 277,000 pounds of contaminated soil. Wetlands have been established to provide wildlife habitat and to help mitigate flooding. This site will eventually be developed according to a masterplan as “Yorklyn Village.” And when the local trails system is complete and connected, the former NVF sites at Yorklyn and Kennett Square will be just a beautiful bike ride away from one another.

Kennett’s story is more complicated. The production of circuit boards and other products made of vulcanized fibre left the Kennett NVF site contaminated with PCP (pentachlorophenol, a carcinogen) in addition to zinc chloride and other contaminants used, for example, in the coating for circuit boards. DVDC has cleared the site of its unsafe structures and with approval from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection has been in the process of cleaning the site of its contaminants in preparation for development. A clean-up was completed to EPA standards around 2016, and when the EPA changed their standards from 9 parts/million to 7 parts/million, the clean-up had to be redone. The Borough’s Historic Commission asked that the water tower remain as a marker honoring the Borough’s industrial past.

While the past can’t be undone, it’s up to us to learn to live with these legacies, to honor what’s good, and to reuse and rehabilitate places like this site responsibly. When it’s declared ready for redevelopment, this 22-acre tract of land between Mulberry Street and the railroad tracks will connect to the town’s street grid as well as to the trail system and offer 22 acres of potential to impact people’s lives in a positive way. A new neighborhood with a unique and authentic identity would bring wealth into the community on a number of levels—from expanding the tax base and increasing property values to broadening the community’s diversity and strengthening its social cohesion.

Special thanks to Lynn Sinclair, founder of the Kennett Heritage Center, and Teresa Pierce, Interpretive Program Coordinator of Auburn Valley State Park and park interns Lindsay Johnston and Harrison Warren.

Do you or your family have memories or stories of working at the NVF plant in Kennett that you’d be willing to share? Please contact us—we’d love to hear from you.